I closed a Pull Request this morning without merging it. It wasn’t because the logic was flawed or the tests failed. The feature actually worked perfectly in the browser. Visually, it was pixel-perfect.

But under the hood? It was a disaster.

A clickable card was just a <div> with an onClick handler. The navigation bar was a list of <span> elements. The main article content wasn’t wrapped in <article>, but—you guessed it—another nested <div> with a class name that looked like a frantic Scrabble player’s worst nightmare.

Actually, let me back up—it’s February 2026. We have AI agents that can write unit tests and tools that generate entire component libraries, yet we are still fighting the “Div Soup” war. And honestly? It’s exhausting.

I want to talk about HTML tags. Not the flashy new APIs or the latest React 19 server components, but the boring, structural bedrock of the web. Because if you’re not using semantic tags correctly right now, you’re not just hurting accessibility users—you’re actively sabotaging your site’s visibility to the very AI models trying to read it.

The “Button vs. Link” War is Over (And You Lost)

If I had a dollar for every time I saw a <div role="button"> when a <button> would have sufficed, I could probably retire to a nice farm without internet access. But I digress.

Here is the rule. It hasn’t changed in a decade, but somehow people still get it wrong:

- Does it go somewhere? Use

<a>. - Does it do something? Use

<button>.

I tested a “button” implemented as a div on a project last Tuesday using NVDA 2025.4. You know what happened? Nothing. The screen reader didn’t announce it as clickable because the developer forgot tabindex="0". Even if they had remembered it, they probably would have forgotten the onKeyDown handler for the Enter and Space keys.

A native <button> gives you focus states, keyboard interactivity, and screen reader announcements for free. Why write 20 lines of JavaScript to reinvent a wheel that browsers perfected in the 90s?

Landmarks Are Your Best Friend (Okay, Maybe Not Best Friend, But Close)

And screen reader users often navigate by jumping between “landmarks.” If your site is just a flat hierarchy of divs, you are forcing them to step through every single element to find the main content.

I recently audited a client’s dashboard. It was built with a popular UI kit that shall remain nameless. The entire sidebar was just a flex container. No <nav> tag in sight.

By simply wrapping the sidebar in <nav> and the primary content area in <main>, we saw the Time to Interactive (TTI) for screen reader users drop significantly during user testing. They could skip the 45 links in the header and jump straight to the meat of the page.

The Tags You Should Be Using

<header> and <footer>: These aren’t just for the top and bottom of the <body>. You can use them inside an <article> or <section> too. A card component often has a header (title/avatar) and a footer (actions/stats). Mark them up that way.

<aside>: Use this for content that is tangentially related to the main content. Sidebars are the obvious use case, but I also use it for “Read More” links or callout boxes within an article.

<section> vs <article>: This one trips people up. My heuristic is simple: Could this block of content stand alone on an RSS feed? If yes, it’s an <article>. Is it just a thematic grouping of content within a larger page? It’s a <section>. If it’s just a wrapper for styling? That’s where your <div> finally belongs.

The AI Factor: It’s Not Just About Humans Anymore

But here is the part that usually gets stakeholders to listen. In 2026, a significant chunk of your “traffic” isn’t human. It’s AI agents—LLMs scraping content to answer user queries directly, or automated assistants booking appointments.

These models rely heavily on the semantic structure to understand context.

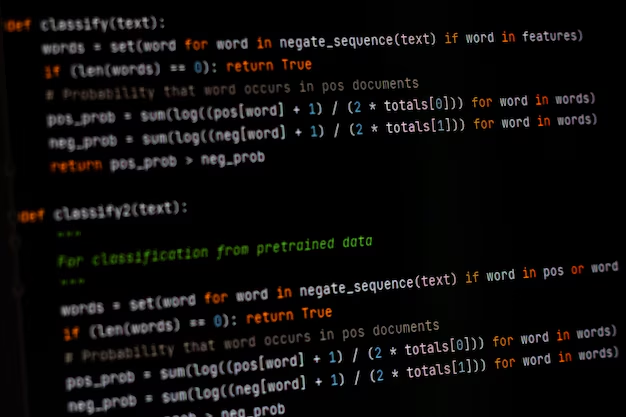

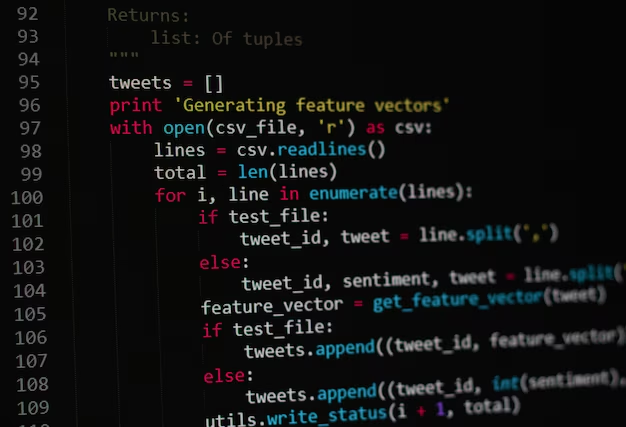

I ran a quick experiment last month. I spun up two versions of a product page.

- Version A: Semantic gold standard.

<article>for the product description,<dl>(definition list) for the specs,<data>for the price. - Version B: Div soup. Everything flattened.

I fed both to a local LLaMA-3-based scraper I use for testing. Version A’s data extraction was 100% accurate. It identified the price, the SKU, and the specifications instantly. Version B? It hallucinated the price because it grabbed a “suggested product” price from a nearby div that looked structurally identical.

If you want your content to be consumed accurately by the next generation of search and assistance tools, semantic HTML is your API definition.

The “Details” That Matter

There are a few tags that I feel are criminally underused.

<details> and <summary>: Stop building custom accordions. Please. The native element works without JavaScript. It’s accessible by default. I ripped out 4KB of JS from a legacy project last week just by switching to this native element. It felt amazing.

<dialog>: Remember when we needed massive libraries to handle modals? Trapping focus, handling the ESC key, managing z-index wars? The <dialog> element handles 90% of this natively now. If you’re still importing a 50KB modal library in 2026, we need to talk.

<output>: If you have a calculation on your page (like a shopping cart total or a mortgage calculator result), wrap it in an <output> tag. It announces updates to screen readers automatically. It’s a tiny detail, but it makes the UI feel so much more responsive to assistive tech.

It’s About Craftsmanship

I know it’s easy to just type div. It’s short. Emmet expands it automatically. It has no default styling to fight against.

But writing HTML is the architectural phase of frontend development. If you build a house with cardboard walls (divs) instead of load-bearing beams (semantic tags), it might look fine with a coat of paint (CSS), but it will crumble under stress.

And next time you’re about to commit a component, take ten seconds. Look at your render method. If it looks like a soup of generic containers, ask yourself: What is this actually? Is it a list? A heading? A navigation block?

Label it what it is. Your users (both human and machine) will thank you.